Wouldn’t it be cool if… A neat way to handle that would be… Ohh, this rule would be interesting… Maybe when defending a character could… Maybe when working together characters could… So many good ideas! I am just drowning in them!

Options, exceptions and little rules can add depth, story, interest, and strategy to a game engine. When designing something like an RPG, which traditionally have fairly lengthy rule sets, a thought sits in the back of the mind: this is only a small exception, this is only one extra option, this little rule works seamlessly with the rest of the system. The slow addition of complexity is the rules creep…

I’ve hit the stage with the fantasy RPG I’m working on where it’s time for the rubber to hit the road, as it were, where characters are created and dice are rolled. Sure, I’ve tested along the way, but it was isolated, not a holistic picture. In recent testing however, I have come to realise I may have added too much, I may have been subjected to rules creep. A good meal is spoiled with the addition of too many spices, and I may have walked that path here…

The question sits, uncomfortable and demanding attention: are there are too many times when players need to reach for the dice? Or must apply a special trait or ability? Or need to compare some result with some other thing? I suspect the answer is yes. Experience tells me that if I ‘suspect’ I ‘may’ have done a thing, I have most definitely done the thing, and that the thing needs fixing.

It was easy to get to this position, it always is. In the writing and development process it’s ever so easy to add just one more thing, or to develop a concept and then take one step further exploring a cool idea related to it. It’s a more difficult thing to work out how much is too much, when the game starts feeling like a procedure and the story takes a back seat to the interplay of mechanisms. In my ideal game the rules are easy and the exceptions few, the story takes the front seat and the players attention is almost wholly dedicated to the development of it. When things need to be checked, or mechanical systems employed, the rules are taking center stage. This is not ideal.

And yet, by the same token, rules exist to add flavour to the story being created by both adding an element of risk (am I going to succeed), and as the vehicle through which the setting and themes of the game influence the direction the story takes (leaping from the rooftop to the ground will surprise my foe (as opposed to shatter my legs)). Exceptions and rules detail add all this flavour in, they provide the internal physics that govern the world in which the story will take place. Rules are important, but too many, or ill applied, brings the risk of derailing the flow of a game by miring the players in the procedure of playing it.

When I worked on miniatures games I often considered exceptions and little rules (short hand for rules that modify the core system), let’s call them complexities for short, to come in two broad varieties: front loaded, and back loaded. Front loaded complexities, to my mind, are the variety that often appear as ‘rule 12.2a’… Everything bundled together, and the exceptions, additions, bonuses, and negatives always applicable: a part of the core rules, all there, up front. Back loaded complexity seek a similar level of depth, but usually only apply if a character or model has a special ability (or, insert game specific parlance here), and therefore only really need to be remembered by the person in control of that character or piece. The core rules are explained, and are usually relatively simple, and the complexities are back loaded as abilities and powers that apply on a case by case basis known to the player to whom it is relevant. In short: front loaded rules are a detailed encyclopedic description of how everything functions from start to finish, and back loaded rules are a simpler core engine, with a range of exceptions tucked away as special abilities or powers.

Using this simplistic dichotomy, I prefer back loaded rules, a simple core engine, where detail and depth (if required) are to be found in exceptions applicable only to characters/players if they have access to them, and they’ll know if they do. Having too much back loaded though, makes a game just as obsessed with minutia as the most detailed of front loaded systems, and of course, the lines are blurred because that’s how lines are.

The balancing point for either approach, to my mind is: how much adds depth and interest, and at what point does the added complexity cause the game play experience to veer into procedural ‘fact checking’ or so much die rolling that the the progression of the story (all about action and outcome) takes a back seat to performing the functions of the rules?

There is no real answer to this question, as every game sets out to achieve something different, and employs a mechanical system to approximate that sought after ‘feeling’ as best the designer/s is/are capable of. Every player will have a different take as well as different preferences, and this whole issue veers into the ‘simulation’ versus ‘narrative’ discussion in RPG design.

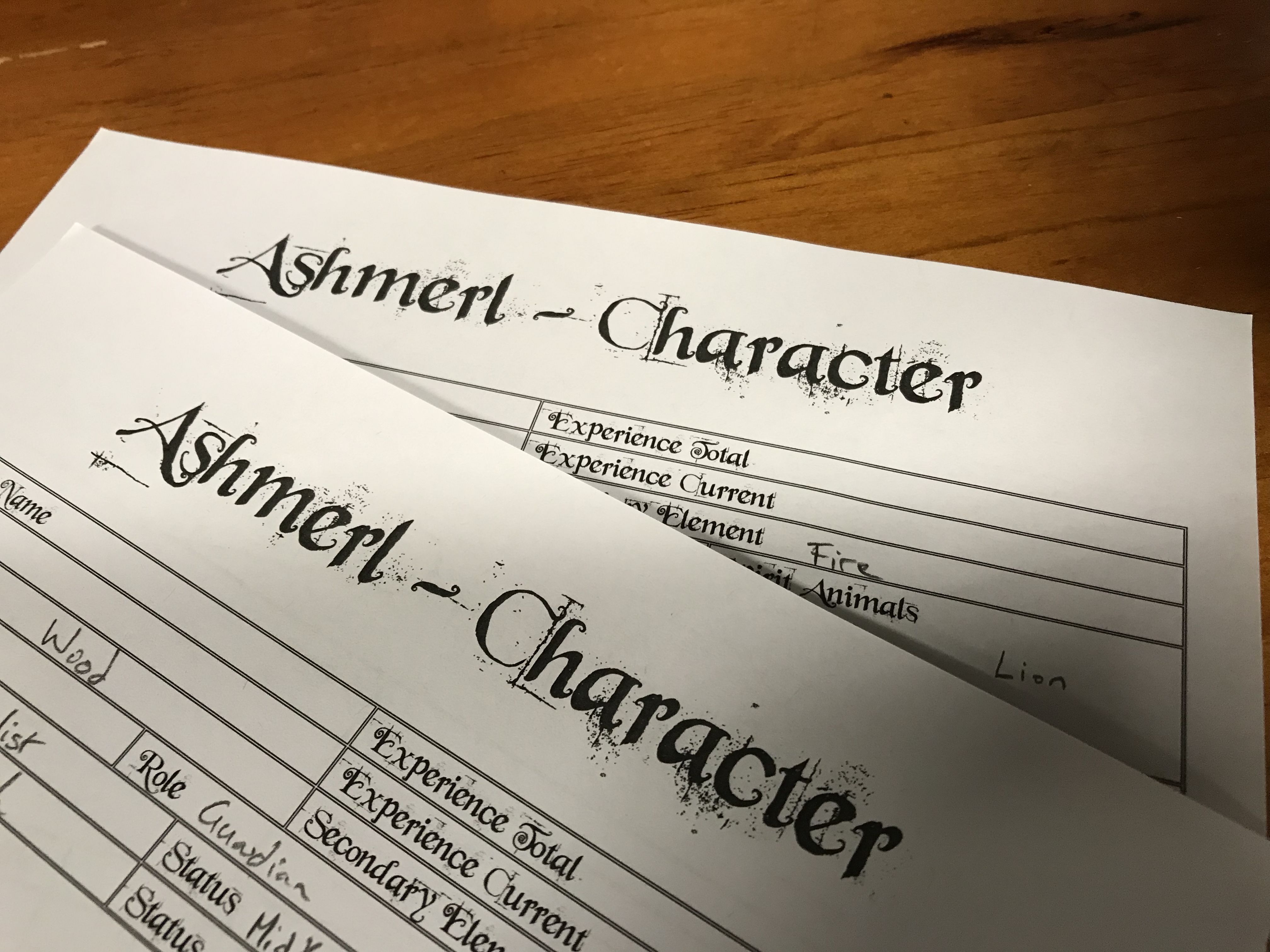

For me, the first words I wrote down as I sat to flesh out the concept of Ashmerl were: ‘A simple rules system where story takes pride of place.’ A lot of things I have added in over the course of development and writing so far have been cool, some of them I am really proud of. I know, however, that much of this will have to go. This is a natural part of the development process for me, and I’m sure others. Design a thing, put it all in, follow the rabbit holes, see where they lead. There are cool ideas in there for sure, but the next step, which sits alongside playtesting, is the ‘great culling’. The part of the process where I must go back through and pare back the layers I have added till the system feels right – till the mechanisms of play are something that drives and adds to the story playing out, rather than chaining it to the detailed or laborious procedure of playing it.

An experiment with watercolours to get a feel for how I want to visualise the setting…