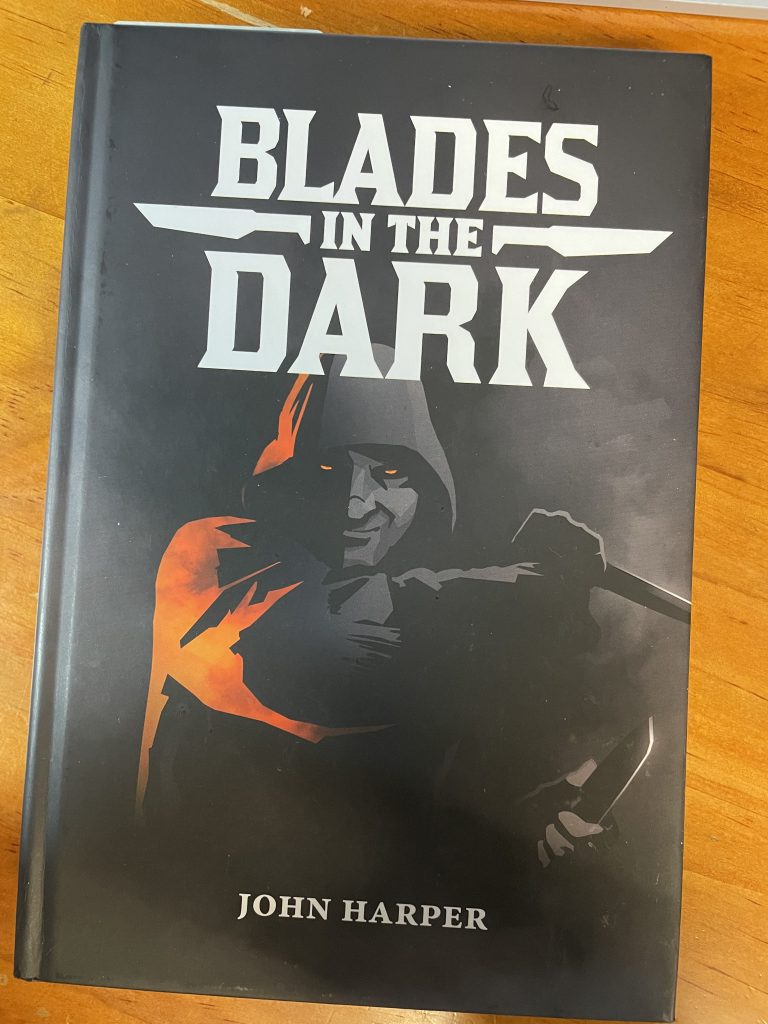

The time has come. I will be running Blades in the Dark soon. This is a game I have loved the sound of for some time, it’s a game I’ve had on my shelf for some time, and it’s a game I’ve looked forward to playing/running for some time.

Famous for the use of clocks, a clever mechanism for tracking extended tasks, background effects, or pretty much anything else your creativity can apply it to (which seem to have originated in Apocalypse World, but really come to life in BitD). Blades in the Dark strikes me as the game of clocks for another reason: it is game system that feels like a set of intricate and interacting cogs and wheels.

Blades is undoubtedly a clever game, it is well designed, and I love the intricacies that seem to flow out of the system (I am yet to run it – this is a view after reading the rules only). It feels like a deeply thematic game, and one where every mechanism feeds into creating a style of play that fits its very evocative setting.

But…

I’ll be the first to admit: I am pretty terrible at reading rules. I rarely read a full rules book, even for games I have run extensively. I too often skim read, skip sections, and don’t bother reading whole sub-systems until I need to know them, and even then, well, see above. I am not a huge fan of crunchy and detailed rules sets. At the same time I absolutely love games that lean into their themes and settings. Blades pulls me in two different directions. On one hand the many many interacting elements have my brain screaming at me to back out while there is still time. On the other I am deeply curious and almost morbidly fascinated to see how all the little wheels look when spinning together.

This is not meant as a criticism of John Harper or Blades in the Dark by any means, Blades reads like a piece of masterful design, and I admire what it sets out to do immensely. It’s just that over the years my tastes in role playing games have leaned further and further toward smaller games and simpler systems.

I fully intend to run the game, my game group is excited to play it, and I am excited to run it. But every time I pick up the rules book a part of my mind cries out in desperation. Why? Because this is not the sort of system I typically like to run. At the same time it is exactly the sort of system I like to run. Go figure.

Blades in the Dark is a clock. All the little cogs and wheels so intricately placed together look like they work as one. Spinning or tweaking one feels like it will affect the whole piece. I am excited to see it in play: to leverage this to alter that, to turn one cog to see what happens to the wheel, but I am fighting myself to get there, my mind telling me to put the book down and find something else to do.

At some point I’ll have to revisit this post and write about how it all goes down. Hopefully well… like a clock ticking down, it’s only a matter of time before I find out!